Solutions to Waterproof Leak-Prone Transit Systems

For transit agencies across the country, water leaks are a source of persistent frustration.

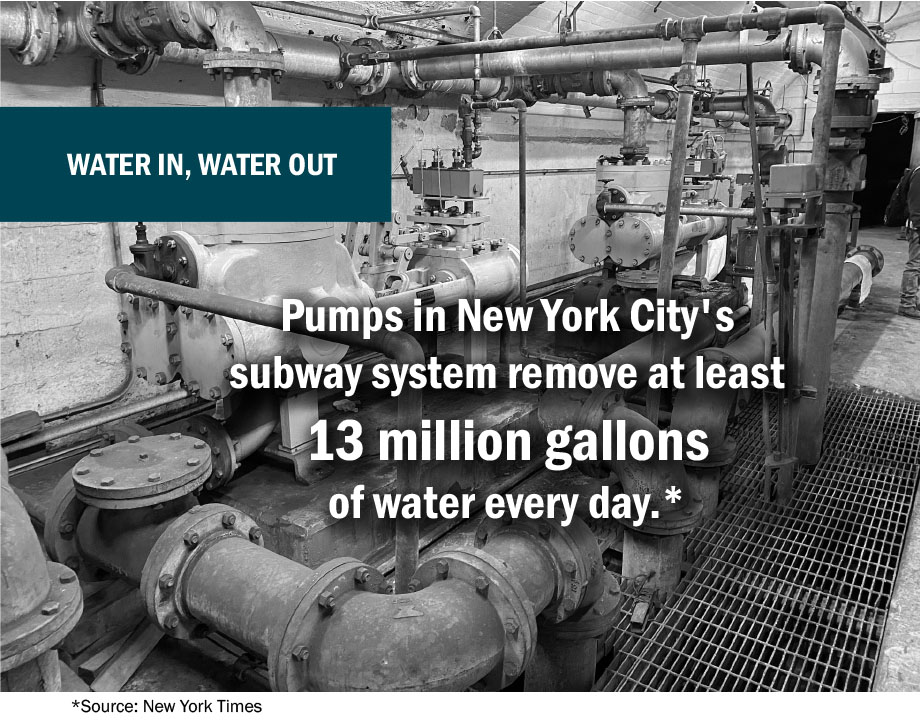

Operators of the largest mass-transit systems wage constant battles to prevent groundwater from leaking onto tracks or seeping within the stations. Millions of dollars are spent every year. Still, climate change projections suggest the costs may continue to rise.

In response, transit agencies are looking to abandon reactionary measures of the past. Rather than attempt to halt water infiltration, pump out accumulated water, and repair the damage, agencies can extend the lifespan of subway systems and related underground infrastructure through custom programs that pilot new technologies and train maintenance staff on emerging best practices.

Waterproofing Challenges Old and New

Modern subway systems are built to withstand typical levels of stormwater or groundwater. Geotextile barriers direct stormwater to drainage systems where it is pumped back to the surface or collected through a stormwater management system. An additional water-resistive layer coats the structure walls and roof, effectively preventing infiltration.

Older subway systems are typically not fully waterproof. Short-term water exposure is managed using gravity-fed drains or pressure-relieving openings within walls. The naturally porous concrete structures often lack protective barriers.

Transit systems traditionally rely on mastic-type protection, such as coal-tar pitch. Although these systems may now be considered obsolete, many materials can still be highly effective in preventing water penetration. However, decades of changing urban landscapes have inadvertently pierced through waterproofing layers or obstructed infiltration-mitigation systems.

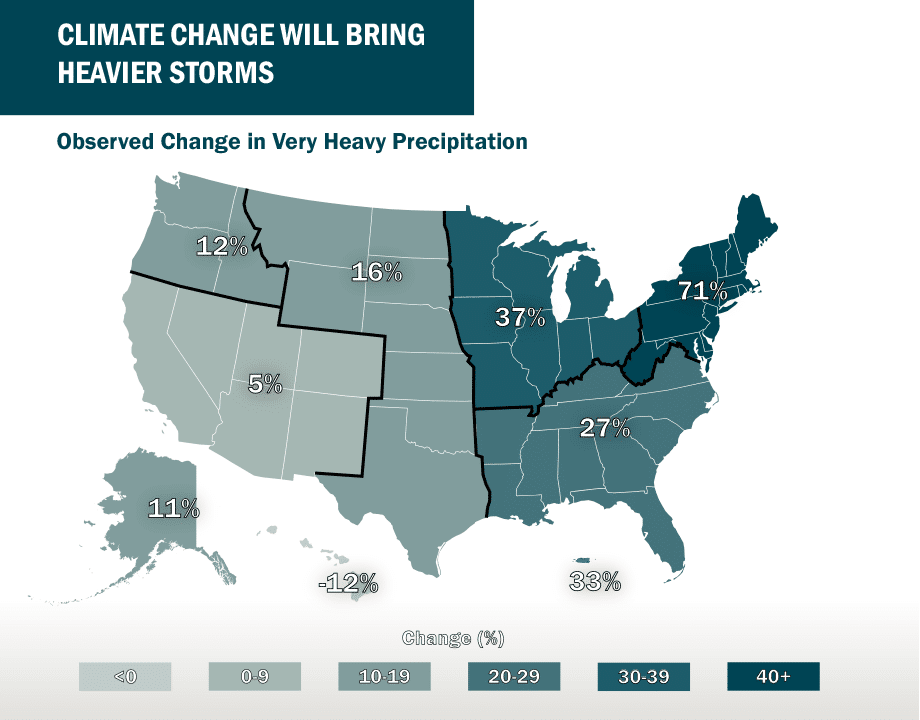

Climate change is expected to exacerbate water damage. The frequency of heavy storms risks undermining transit assets, threatening state of good repair goals, and complicating the reliability and safety of operations.

As more-intense rainfall channels stormwater into aging tunnels and stations, the loss of natural landscapes means fewer opportunities for ground infiltration. A lack of drainage options places greater demand on stormwater and waterproofing systems, further exceeding their intended capacity.

Maintenance and Safety Consequences

When intrusion occurs, water usually leaks through cracks, voids, or construction joints. Over time, potential damage includes:

- Spalling of concrete,

- Corrosion of structural steel and reinforcing steel,

- Corrosion of track beds and cables,

- Damage to finishes,

- Pooling of water around mechanical and electrical components, and

- Accumulation of mineral deposits that can undermine mechanical and electrical components.

Water infiltration can also pose a hazard for workers and the public alike – resulting in preventable slip-and-fall incidents.

The Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority (WMATA) has long waged a battle to address water infiltration. The oldest section of the Red Line, for example, sits below the groundwater table and relies upon pumping stations that, under normal circumstances, remove millions of gallons of water per week. A $12 million WMATA waterproofing program has significantly reduced track damage and improved operations.

Taking Control of Water Infiltration

The first step in reducing water infiltration is to perform a comprehensive leak investigation. Once leak sources are identified, transit agencies must decide whether to approach the problem from above or below the surface.

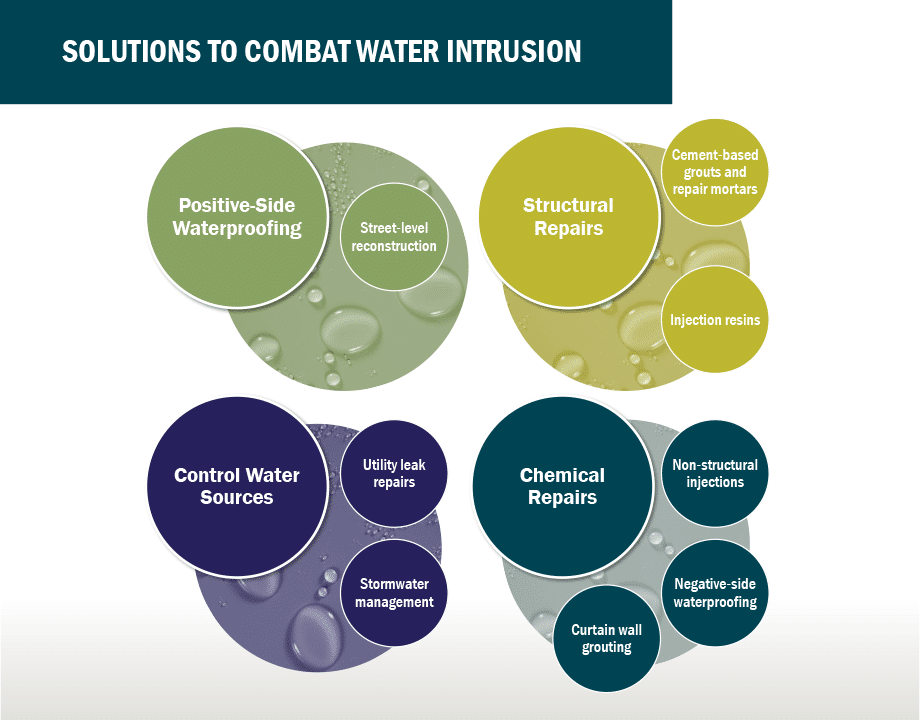

Combined with proper stormwater drainage, positive-side waterproofing can generally be the most-effective, reliable, and longest-lasting solution. However, traditional rehabilitation can come at high costs.

Any excavation or reconfiguration of dense urban landscapes can be highly intrusive for commuters, adjacent properties, and roadway travelers. Abandoned utility lines require capping and removal, while active lines can require rerouting or re-evaluation of the underground structure’s waterproofing strategy. Utility conflicts inevitably drive up project costs and cause construction delays.

Additional construction risks are presented when agencies must coordinate with private property owners and co-located agencies, potentially adding new costs, delays, and public relations outreach.

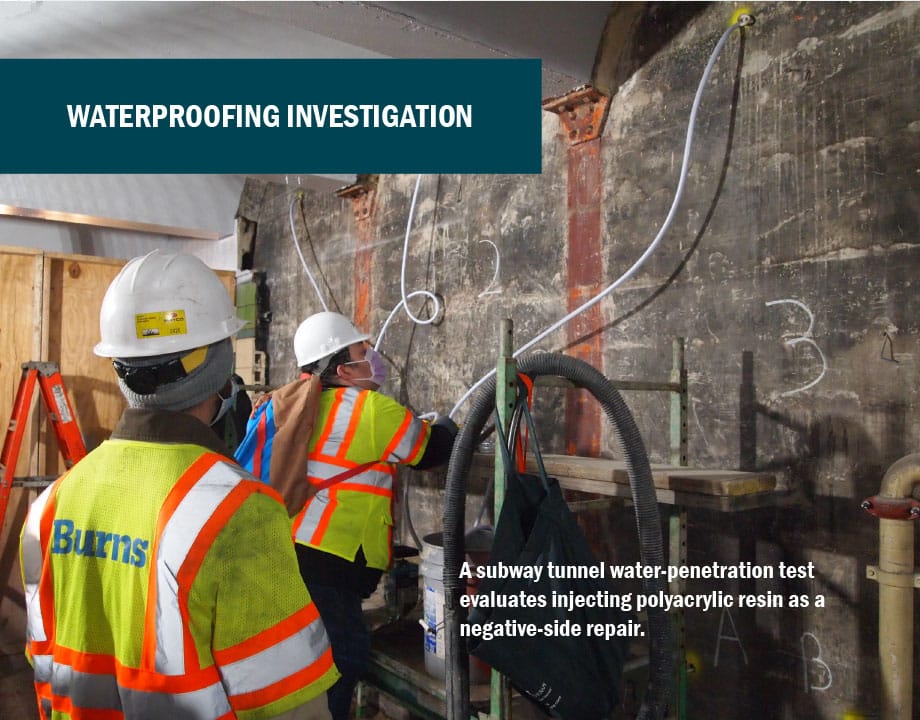

An alternative approach involves below-ground, negative-side waterproofing that redirects water by attacking it from inside the subway tunnels. Patching leaks at accessible locations can be easier and much-less expensive. Some methods, however, have notoriously halted infiltration for only a few months or simply redirected the water to a crack located nearby.

A third option utilizes a hybrid system of a positive-side water barrier, known as a grout curtain, installed from within the subway structure. These systems are installed similar to a negative-side injection, methodically installed to create or restore a complete positive-side water barrier.

Responding to the Insidious Threat of Water Damage

Identifying the proper waterproofing strategy starts with careful evaluation of the water’s path and a review of which structural or chemical solutions can provide the longest-lasting, most-economical repair.

Waterproofing through chemical injection offers tremendous potential over the high-failure crack injection methods of the past. Still, a menu of options often needs to be combined to ensure agencies apply the proper fix to the unique challenges of each particular station or track section.

A reliable maintenance plan and repair strategy may involve targeted testing. With new technologies developing every year, the consulting engineer should invest the time and resources necessary to research the best possible solution.

In addition, waterproofing design cannot be founded on experience alone. Waterproofing investigations must take into consideration the service area’s hydrology, the infrastructure’s state of repair, feasibility of structural excavations and redundancy measures, and available funds.

Benefits for transit agencies that commit to undertaking custom waterproofing solutions can include:

- Avoiding the need to perform repeat injections or repairs, generating significant maintenance savings,

- Lessening the burden on often-overwhelmed pumping systems,

- Improving passenger safety,

- Preventing costly damage to advanced communications technologies, and

- Positioning transit systems to be more resilient in the face of intensifying storms and/or rising groundwater.

Most important, by developing less-intrusive, longer-lasting waterproofing strategies, transit agencies can control capital costs, minimize disruption for commuters, and keep riders safe, dry, and on-the-go for years to come.