Guide to Zero-Emission Transit Vehicles

Transportation-sector carbon emissions are on the rise, accounting for more U.S. greenhouse gas emissions than any other source.

In response, transit agencies, municipalities and private fleet operators are doing their part, transitioning away from fossil fuels and embracing a new generation of zero-emission vehicles (ZEVs).

Burns recently completed a life-cycle analysis of various ZEV options for a regional transit agency, reviewing whether environmental benefits and operational cost savings justify higher upfront infrastructure and vehicle-acquisition costs.

After comparing plug-in hybrid, battery electric and hydrogen fuel cell options, the takeaway is clear. Although the total cost of battery-electric buses (BEBs) remains slightly higher compared to hybrid vehicles, BEBs are the most cost-effective option today for reducing bus transit emissions.

Battery-electric buses are the most cost-effective option today for reducing bus transit emissions.

As vehicle technology continues to advance — battery costs are declining while range and reliability are improving — fleet electrification benefits are likely to accelerate.

Sizing Up the Market

The medium- and heavy-duty vehicle (MHDV) market is on the cusp of an electric transformation. While this article will focus specifically on transit buses, increasingly fleet operators are driving toward new models of ZEV semi-trucks, delivery vans, garbage trucks, utility maintenance vehicles and much more.

The electrification trend is fueled not only by technology advances. Speeding up the transition are significant federal and state financial incentives. Mandates are in place in California and being proposed all across the country.

Electric bus at a charging station on a city street

Transit agencies servicing New York City, Los Angeles and San Francisco have all committed to ZEVs by 2040.

A 2019 transit agency survey by CALSTART counted at least 202 agencies operating 2,255 zero-emission buses — a 37-percent increase over the prior year.

California agencies own 45 percent of the U.S. fleet of ZEVs (1,016). Others are scattered across the country, led by Washington (211), Florida (142), Colorado (73) and Illinois (73).

Battery power accounts for 97 percent of ZEVs in operation. Hydrogen power makes up the rest, with fuel cell buses (FCBs) currently operating in California (52) and Ohio (12). An additional 30 fuel cell buses are under development.

Looking ahead, ZEVs are forecast to grow from 20 percent of global bus fleets to more than 60 percent by 2040.

Comparing Options

When analyzing ZEV options, Burns compared the life-cycle cost of BEBs and FCBs to hybrid-electric bus (HEB) alternatives. HEBs are powered by an internal combustion engine and an electric motor, using regenerative braking to keep the battery charged.

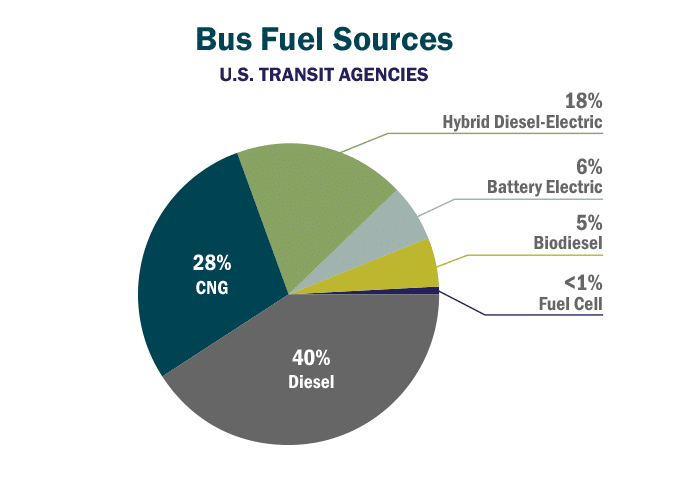

Today, HEBs are the most commonly purchased option when replacing or expanding bus fleets, accounting for about 18 percent of all transit agency buses, according to the American Public Transportation Association.

BEBs utilize batteries to store electrical energy that powers the bus motor and onboard equipment. Of the two dozen BEB manufacturers worldwide, six offer 40-foot products available for purchase by U.S. transit agencies and two offer 60-foot options.

Common BEB charging solutions involve plug-in, pantograph and induction (or wireless) options.

FCBs are also electric vehicles, fueled by hydrogen gas stored for propulsion in a fuel cell rather than a battery. Transit agencies can choose among three 40-foot FCB models.

Pure hydrogen does not exist freely in nature. Instead, hydrogen can be produced in a variety of ways including thermal, electrolytic, solar-driven or biological processes. The hydrogen can either be delivered or, less economically, produced on site.

Costs and Implementation Barriers

ZEV challenges involve issues of range, cost and operational concerns.

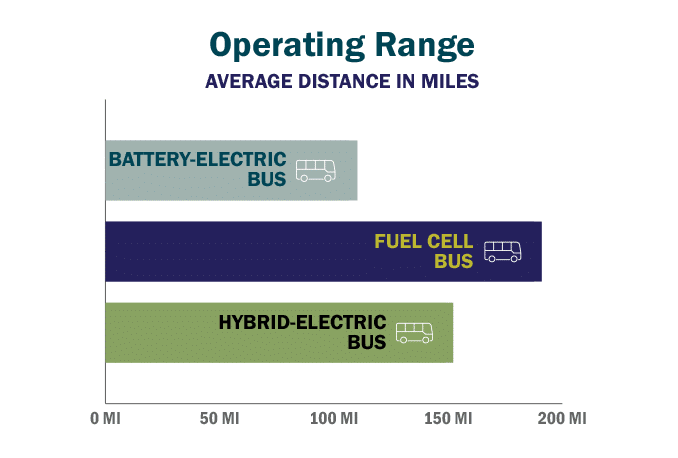

How far a ZEV can travel on a single charge is the predominant concern for transit agencies. Rightfully so. Each agency must analyze pilot program routes and determine whether their vehicle of choice can seamlessly manage the transition, upholding the reliability and resiliency of current bus operations.

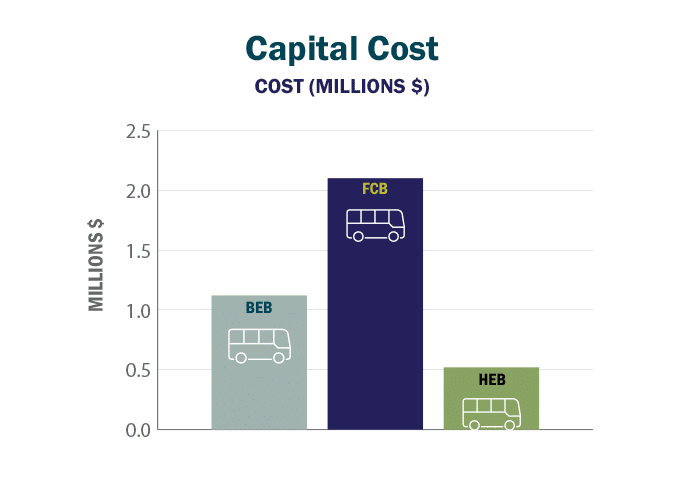

Conditions that impact operation range include battery charge or capacity, the route’s terrain, climate and the frequency of stops, as well as energy consumed by the ZEV’s heating, ventilation and air conditioning (HVAC) equipment. At a time when the coronavirus pandemic is severely reducing transit agencies’ operating revenue, keeping upfront costs to a minimum is more important than ever before. Our analysis looked at average costs to purchase and charge each vehicle type, assuming equal level of available federal funds.

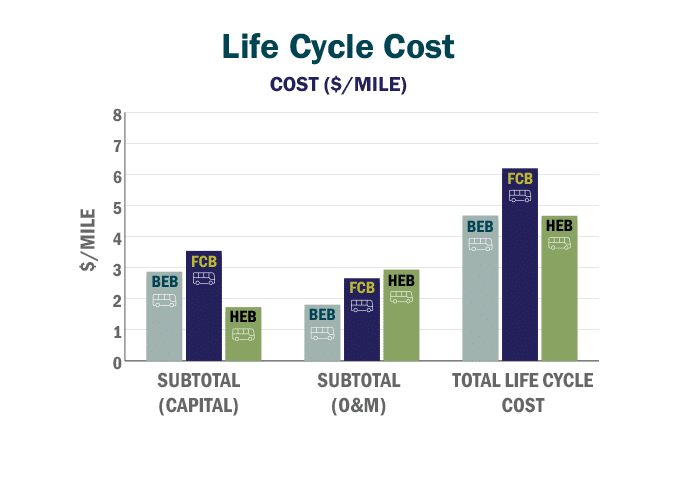

On average, BEB capital costs are more than 65-percent greater per mile than HEBs. But FCB costs are higher still — on average, 105-percent more per mile, compared to HEBs.

Other operational concerns pertain to depot infrastructure constraints, variations in seating capacity and “disposal” (or resale) options at the end of the vehicle’s service life. Each are accompanied by important financial considerations.

Financial Benefits

Properly managed, BEB charging costs are considerably lower than the cost to refuel FCBs or HEBs. Attribute that to the fact that much of the heat generated by FCBs or HEBs is lost through wasted energy.

That said, time is money. BEB charging requires more time, potentially impacting operation schedules.

To factor these in, our life-cycle analysis combined infrastructure maintenance, fuel and vehicle maintenance costs. FCB operations and maintenance (O&M) costs are, on average, nearly 10-percent lower per mile than HEBs. Savings for BEB operators are even more significant. O&M costs are lower by more than 34 percent per mile, on average, compared to HEBs.

Added to the total capital cost, our analysis finds that FCBs have the highest life-cycle cost. Between BEBs and HEBs, the cost difference is relatively insignificant.

Environmental Considerations

ZEVs are cleaner and quieter.

BEBs and FCBs have no tailpipe emissions. By cutting down pollution of nitrogen oxides, ozone and particulate matter, transit agencies can make a serious impact improving overall public health. Benefits will likely be especially noticed among low-income communities and communities of color who are disproportionately exposed to air pollution.

Calculating climate benefits is more complicated.

No greenhouse gas emissions are associated with BEB operations, provided the charging system is powered by renewable energy. More often, however, the electric grid relies on fossil fuel. As the electric grid transitions to cleaner sources of energy, the environmental benefits of BEBs improve as well.

Other environmental factors depend on how minerals are extracted to create vehicle battery packs. Lithium is relatively benign, available from natural brines, ore or seawater. But production of more-powerful batteries containing nickel or cobalt can result in high levels of air, soil and water pollution. Battery disposal processes will eventually need to be developed as well.

The environmental footprint of FCBs are complicated as well. Hydrogen is produced mostly by converting natural gas into hydrogen gas and carbon dioxide. Trucking fuel to a filling station produces even greater emissions. If transit agencies invest in on-site, renewable energy generation, fuel can be produced with minimal environmental impacts.

One environmental benefit will be noticed relatively quickly. Replacing combustion engines with batteries creates a quieter ride for passengers and minimizes noise along the route.

Making the Right Choice

After years of development, ZEVs may finally be ready for widespread adoption.

Though upfront costs and operational transitions may seem daunting, technology improvements suggest financial returns are within reach. Savings from BEBs can yield a positive payback — perhaps within a decade or less, depending on the availability of incentives and each transit agency’s unique operating costs.

Regardless of financial savings, the environmental benefits will be significant. Each ZEV that deploys into service demonstrates a commitment to addressing climate change, air quality and environmental justice concerns.

For transportation leaders looking to solidify their role as environmental leaders, now is the time to get on board. The ZEV ride is about to begin.