Utilities Increasingly Embrace Microgrids

For years, utility companies by and large viewed microgrids as a threat to their profitability. Those views are now changing.

Utilities and regulatory bodies are beginning to embrace the evolving energy production, storage and distribution technologies as key to their own financial sustainability.

The shift comes as increasing competition from distributed energy resources and energy efficiency threaten their more traditional business models.

The United States suffers $150 billion in economic losses every year due to power outages.

Microgrid Benefits

Microgrids are independent, self-sustaining, decentralized energy systems that power distinct buildings, campuses or geographic areas. The concept has been around for decades. However, a number of factors has coalesced in recent years to make microgrids and the distributed power sources that feed them less expensive, more efficient and more reliable.

The quickly evolving technology associated with controlling and distributing renewable energy has become almost mainstream. Renewable solar power is more affordable today than ever before. Developments in inverter technology and battery energy storage have transformed solar energy to become much more resilient and reliable.

Simultaneously, microgrids bring tremendous value in maintaining critical power during severe weather such as hurricanes, wildfires or other catastrophic events. Microgrids operate to provide power in these times of need, replacing traditional utility power.

For example, during the recent Texas power outages, at least 130 microgrids supplied power capacity. Microgrid-powered facilities stayed open, supplying groceries, prescriptions and gasoline. Across the region, hundreds of stores that rely on the traditional grid remained closed days after the storm passed.

During the Texas blackouts, microgrids powered buildings such as gas stations, department stores and a 300,000-sf pharmaceutical manufacturing facility.

Microgrids do not simply provide power when utility power is unavailable. Additional services include providing value in use cases to the utility such as substation or feeder demand management. The microgrid can reduce its import of power to help alleviate congestion on the grid.

Utilities and regulatory bodies are evaluating microgrids as potential non-wire alternative solutions to supply power to new developments in areas that are logistically challenging or too expensive.

Congested urban areas look to microgrids for on-site power generation.

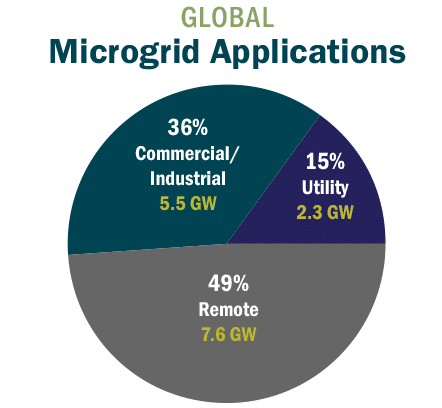

Remote, rural areas are especially beneficial applications in instances where installation of overhead or underground wires is logistically challenging and very costly. Congested, built-out urban areas are also turning to microgrids in situations where installing new lines may be more challenging than on-site generation solutions.

Microgrids can support other growing sustainability initiatives, such as delivering power to charge fleets of electric vehicles. Fleet charging will likely require significant power at facilities that simply do not have the existing capacity to support them. By deploying microgrids at these electric fleet sites, these developments can have a proper mix of utility power, renewable and resilient power.

The Utility of the Future

For all of these reasons, an increasing number of utilities are considering microgrids as a component of their “utility of the future.”

While each state differs on whether and how utilities can install and use them, microgrid projects are proliferating in both the U.S. and abroad. North America leads the world in terms of total capacity, followed by Asia Pacific and the Middle East and Africa.

Navigant Research has identified more than 4,475 microgrid projects globally, representing over 26,770 MW of planned and installed power capacity.

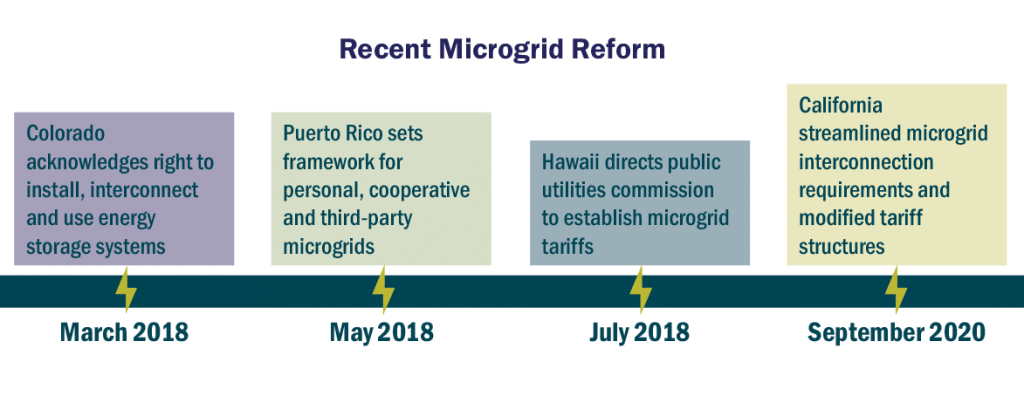

While interest in microgrids is on the rise, regulations and standardization have struggled to keep pace. California, Colorado, Hawaii and Puerto Rico have passed laws allowing microgrids. At least 14 other states have allowed utility providers to develop microgrid pilot programs. California recently moved forward with legislation requiring their utilities to develop microgrid tariffs.

Pathways to a Microgrid Future

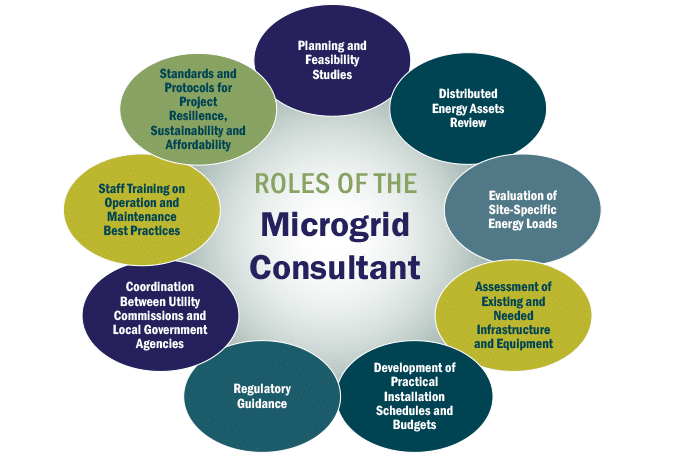

Microgrid development comes with a long set of challenges. Site-specific issues must be considered throughout the design, installation, operation and maintenance phases. Utility providers, state regulators and local municipalities are each likely to impose unique requirements.

That said, the influence of regulatory oversight varies from state to state and region to region. Projects completed to date have been highly site- and client-specific, making development of industry-wide standards elusive.

Prudent utilities have been launching pilot programs to test microgrids for efficacy, efficiency and scalability. With these real-world results, more are able to convince regulatory commissions to grant them a greater share in an exploding market.

Utility providers, property owners or municipal agencies looking to develop a microgrid program should seek an engineering partner who can serve as a guide throughout the various planning, design and technology challenges. Properly managed, a successful microgrid project should fulfill its promise of resilience, sustainability and affordability for years to come.

Learn about Burns’ microgrid experience.

Resilient Power and Microgrids